When I was in first grade, I had no idea how the world saw me. I knew I liked to draw, that I loved Science and nature, and that I was shy and introverted, but it wasn’t until we’d gotten our first school yearbooks that I began to understand how I was perceived by my peers. After passing my annual around all morning, I began to see a pattern in the signatures I collected — they all said “To a really good drawer”.

I remember being amazed at this new information I’d gleaned. The thing that made me the happiest was the thing I had become known for! …Not only known, but appreciated and valued. It was not only “okay” for me to be what I felt strongly compelled to be, it was “expected”. This was the role that society had laid out for me, and to fulfill this role felt like the universe coming together. It felt like it was meant to be — like a dream coming true.

From that point on, throughout my childhood, any time I pictured myself as an adult, it was as an artist. Whenever anyone asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, the answer was always “an artist”. When I went to the library, it was to study artists and their work. I read books – biographies, autobiographies, watched documentaries, and absorbed myself in a world that I lived and breathed to inhabit one day.

Even in dreams, I repeatedly found myself in that world. My entire waking and sleeping life seemed to revolve around the idea that I might one day grow into an artist, and live that life.

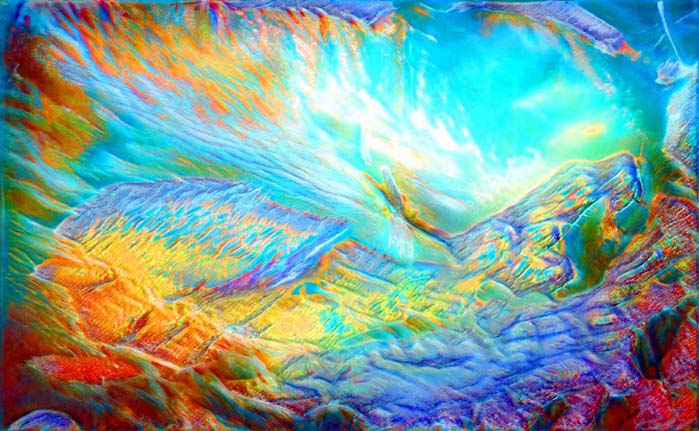

One dream in particular has stuck with me over the years – a flying dream where the land beneath me seemed to hold a secret; as if the hills, rivers, and lakes conveyed some kind of message, if I could only see them the right way. I woke with the overwhelming feeling that I had dreamed something important, but didn’t understand it, let alone how to convey it to anyone.

I set out from that point, to try and convey it to everyone.

…But it wasn’t until my college years that I began to see cracks in the shiny facade.

The time had come for me to choose a major, and of course I chose painting.

My mother was less than pleased.

In fact you can likely imagine what she said. “You can’t make a living doing that!”

She can’t be totally blamed for her concern.

I had planned to apply to be an NEA artist upon graduation, but this was the late 80’s, early 90’s. This was a time when people like Lucas Samaras and Robert Mapplethorpe were making regular headlines in the US (thanks in large part to people like Senator Jesse Helms) for receiving federal funding, in light of their controversial subject matters. The question of Art’s very place in society was on the table, along with the value of the artist.

I was already feeling the impact of all that, but little did I know how deeply it would affect me, nor how much that impact would grow over time.

But unlike most of my peers, I wasn’t in school to burn 4 more years, or to get a better job, or make more money — I was in school to develop a painting technique which was new, and immediately recognizable as my own. It’s all I had dreamed about, my entire life up to that point.

I was extremely lucky for the opportunity to attend college when it was much more affordable, but in addition to that I was lucky in another way: I just happened to take 2 classes at the same time, which were instrumental in the development of my painting style.

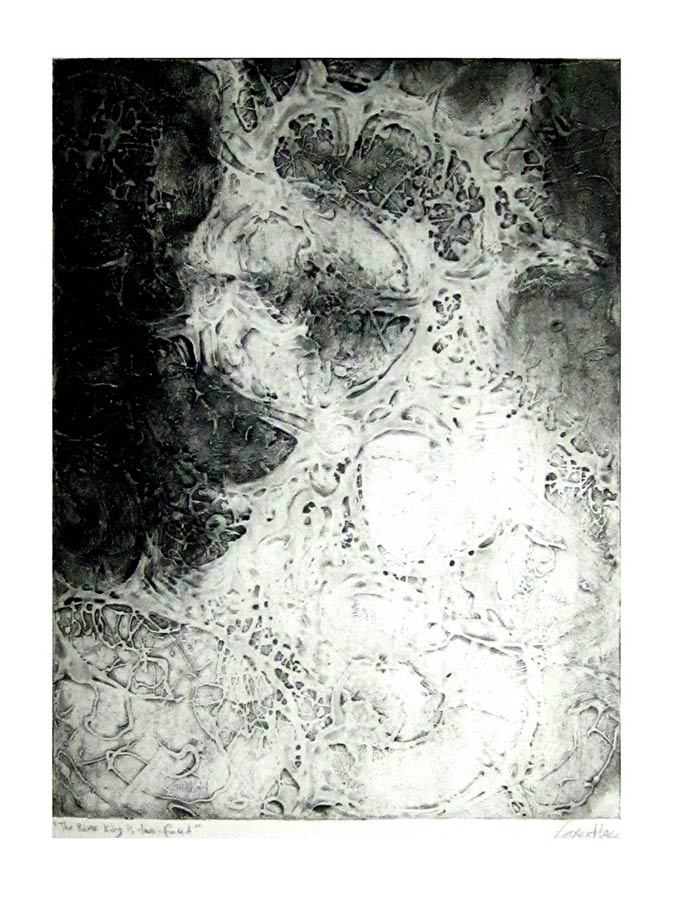

The first one was an introductory printmaking class that featured collagraph printing, or printing using gesso on pressboard plates. Anything added to the gesso could give it texture, and that texture could hold ink for printing.

The printing process would remove most of the ink from the collagraph plate, but leave trace amounts in the recesses. Subsequent re-printings in other colors would yield interesting results, as the scant remains left behind from each layer would interact in unexpected ways. I was instantly intrigued, and began devising ways to increase the dimensions of the work surface.

In essence, my paintings are huge collagraph plates, except that instead of being intended to transfer pigment to paper, they are meant to hold the pigment forever.

…But what about the pigment? Printing ink was clearly not the best choice, I needed something else.

…And that’s where the second class came in, called “Aqueous Media”, or painting with highly viscous mediums. This was the class which gave me the idea of pouring liquid paint over the painting while keeping it horizontal, trapping the paint in the recesses until the water evaporated, leaving the pigment and binder behind. I replaced the mat board with masonite for strength and durability, even when wet.

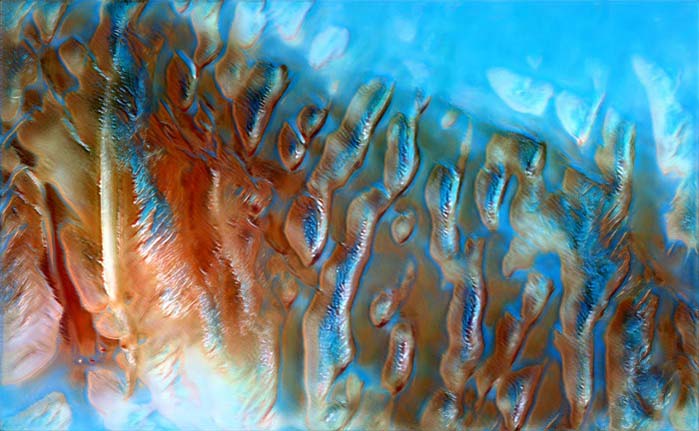

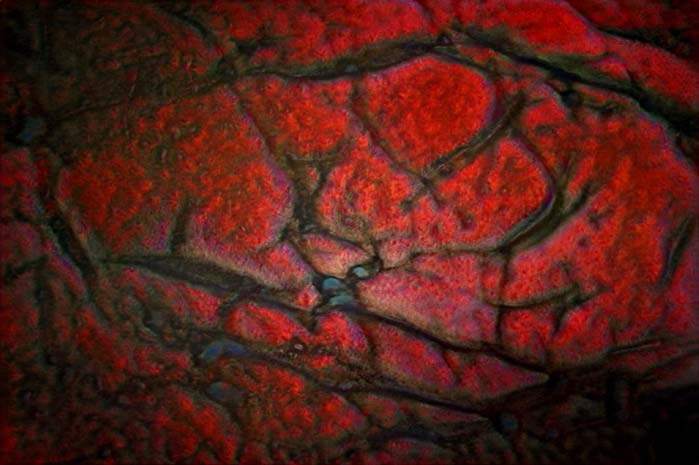

I experimented with just one color at first. I found that deeper areas produced a deeper color due to having more pigment above, which settles at the lowest points, but also creates a gradient which becomes lighter as the elevation rises.

After experimenting with pouring various colors over the dried gesso, I learned that paints with a heavy, large pigment grain deposited their pigment quickly, whereas paints with a fine, lightweight pigment grain required more time in order to deposit their pigments. This meant that areas where the paint flowed quickly deposited less pigment, and areas where it flowed more slowly produced a darker coloring.

I came to learn that this is the same process by which river deltas and alluvial fans are made in nature; by sediment deposition. Some of the same imagery made visible by satellites can be produced on a much smaller scale, by applying some of the same natural processes.

This was the inspiration behind the painting technique’s title: “Natural Process Painting”. Every step along the way, from fractal field patterns in the raw gesso, to the pigment deposition, is an expression of natural processes and mechanics.

This synchronicity with nature was made even more obvious with the addition of more colors, added in layers. If I needed more pigment in an area I can flood it by weighing down that part of the masonite. If I need less pigment I can produce a drought in that area by raising the masonite with wooden wedges. The way the layers interacted was mostly due to the previously mentioned weight and size of the pigment grains, but also due to their opacity. Therefore the order in which layers were added was extremely important.

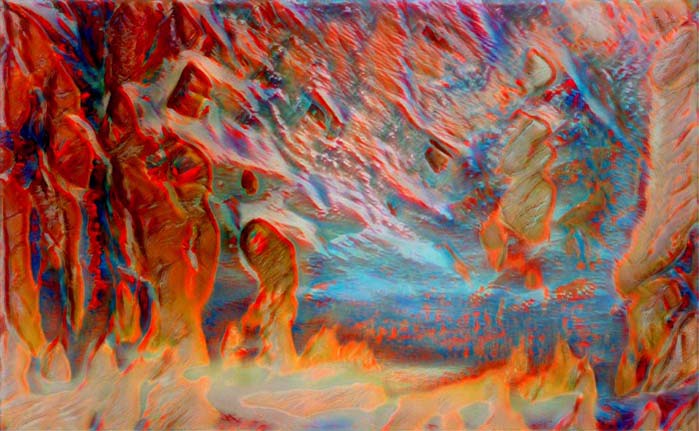

The end result was not only a blending of all the individual color layers, but due to the unexpected ways in which the layers interacted, it was more than the sum of its parts. Those parts all came together to resemble relief maps of my own dream landscapes.

I was far from a master of my own techniques, but was excited about finishing out the remainder of my college years honing those skills and techniques, in preparation for obtaining fed. arts funding (hopefully).

However, all during those years, due to efforts spearheaded by people like Jesse Helms and later Bill Clinton, the NEA was in the process of being “phased out” (pronounced “completely dismantled”) for individual artists. I was graduating into a world in which the state no longer saw any value in the arts, or artists, and no longer sought to invest in them with public money.

I had also just had all of my work from the last 4 years thrown away by someone I knew. …Including this, the largest painting I’ve ever made, at 96″ x 48″. This is the only picture in existence of it.

If I was going to make it as an artist, it was up to me to start over again. There was no higher authority to impress, except for public consensus. I hated living in big cities and longed for the countryside, but felt empowered by how big the internet had already gotten. I felt fairly confident that I would be able to eke out a living as an artist while living anywhere I wanted, since I would be able to sell on the .com marketplace.

…I was extremely naive.

After successfully obtaining online artist representation no less than three times, even signing contracts twice, no “online gallery” that promised to represent me ever wound up actually going online. Once I had finally gotten on with a gallery in Atlanta, it wasn’t long before they went under as well. Things were changing in the art world, especially for artists, and almost none of it was good.

But no matter what else is going on in the world, an artist must keep working in order to stay healthy.

…But that’s hard to do when you wake up one day, and all of your art supplies have changed for the worse as well. …Especially when those changes are industry-wide, across the board.

First it was the paints. “Professional artist colors” that once were 100% colored with pigments, were suddenly only partially pigmented, or not pigmented at all. The rest was just cheap dye in the acrylic medium. There’s nothing quite like paying $15 for a small pot of cadmium red medium, just to watch it roll right off the edge of the painting and into the grass without leaving a single trace that it had ever been there, like a tube of $1 craft paint. It forced me to order my own pigments in bulk, and add them to acrylic medium myself to make my own paints for years, but nothing could have prepared me for what was in store for me with my gesso.

Gesso is and has always been an integral part of the NPP technique. Its porous, flexible, rigid qualities are what give the work a high relief that can be painted on to great effect.

It also once cost $18–$50 per gallon, depending on the brand and where it was purchased. This was up until around the year 2000. About that time, the cost of gesso started climbing to the sky, and the last time I looked Michael’s here in town was selling one gallon of gesso for $125. There was no “off brand” to choose. This “creative tax” is pretty typical, in the great push to make art simply a past-time of the elite.

But that’s not even the worst news, for artists who once used gesso for high-bas relief, or sculptural work: The marble dust which once made the gesso pliable and absorbent has been replaced by cheap chalk dust which shrinks, buckles, cracks, and falls away from masonite almost completely when applied thickly.

I was able to solve the paint problem, but the gesso problem continued to be troublesome. I could match the consistency, but lacked a pressure chamber large enough to get the air bubbles out of an entire gallon of gesso at once. The end result was gesso that looked like oatmeal — again, after experimenting for weeks, at great expense — starting over again from scratch, after 20 years of learning, building and establishing. What once was an exciting, cathartic experience that I looked forward to, was suddenly a frustrating exercise in futility that I dreaded.

What followed was years of deep, profound depression, with very little in the way of creative output. I fought against an oppressive political climate for most of this time by writing, in an attempt to at least improve awareness about what was happening to the arts, and creative people in the US (along with everyone else who wasn’t a billionaire), but without the ability to be creatively productive it became too much for me to maintain.

I was beginning to feel totally lost, for possibly the first time in my life. I felt utterly hopeless, powerless, and directionless. Even social media platforms like facebook, which once was at least a decent way to publish my work, became a pay-to-win wasteland. I had long given up on the “art festival” scam circuit for the same reason. They say “No artist creates in a vacuum”, but I was living in one.

Then around June of 2021, I stopped writing, in order to pursue my art. I started posting on twitter, opensea, and even made a patreon page for my artwork. Even if I posted everything I had, and couldn’t produce new paintings, I could still post drawings, or close-up details of previously posted paintings.

…But that wasn’t going to sustain me forever. I had to find a way to either paint in my original way again, or literally start all over again from scratch. About that time is when I discovered art made by generative adversarial networks, or GAN art, where an AI is “trained” with images of a person’s artwork, to the point that it can produce completely new and unique work that is sometimes indistinguishable from the original.

As of this writing, the hardware required for this training is extremely cost-prohibitive, forcing most (like me) to use paid subscription services to gain access to this hardware remotely. There are several services available, each with its own distinctive GAN outputs, and after subscribing to a couple of them, I was able to train generative adversarial network models using thousands of images of my own paintings, along with details taken at various levels of zoom. The results were unexpected, but my work has always been a compromise between chaos and control. I simply “encourage” chaos to do my bidding, but I am always surprised at what happens when I paint. That is a large part of the joy of it for me. GAN image creation has some of the same joy of surprise, and unexpected discovery.

I will always love actual, real painting more than anything else, but until I can realize a steady supply of my painting materials again, it’s very nice to have this tool. Though there are some who will call me a charlatan for my use of AI to produce art, those AI would have no idea how to make these images if I hadn’t trained them with my own artwork, and I couldn’t have done that if I hadn’t persevered through years of adversity, opposition, and self-doubt to produce nearly 3 decades worth of work to use as training material.

And that is why I’m writing any of this today, to remind you, who may be encountering some of these same issues as an artist, not to give up — and that you are not alone. No matter how talented we may be, or how imaginative, or how fierce and unique, our greatest asset is each other. For no matter how suffocating the current corporate atmosphere is for creative people, or how hopeless it all seems, together we can pull ourselves out of anything.

Good luck, and thank you for reading!

Do you like this article? Support our blog with a small donation.

We keep our contents authentic and free from third party ad placements. Your continued support indeed can help us keep going and growing. By making a small donation would mean we can pay for web maintenance, hosting, content creation and marketing costs for the YDJ Blog. Thank you so much!

How fascinating! I’m so glad you’ve emerged from that tunnel of depression and I also learned a lot. I thought art supplies have been going downhill for a long time but never investigated. It makes me crazy that they penalize those people who have a positive and joyful gifts to give.

What a journey!!! I love your works whichever way you create them. They are truly gorgeous!!!